ken Ofori-Atta, Finance Minister

ken Ofori-Atta, Finance Minister

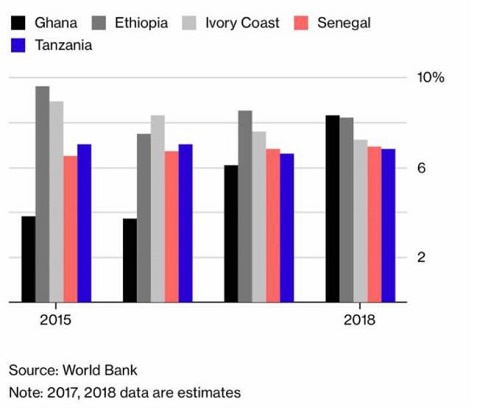

Ghana is poised to take the lead as Africa’s fastest-growing economy this year, the first time in at least three decades.

Expansion in West Africa’s second-biggest economy in 2018 should surpass that of recent champions Ethiopia and Ivory Coast, according to forecasts from the World Bank, and the African Development Bank, which were both released in the past month.

The West African economy is forecast to expand the fastest on the continent in 2018.

Commodities, including oil, gold and cocoa are the mainstay of the $43 billion economy and rising crude output is boosting the nation’s finances.

But a year after the government of President Nana Akufo-Addo took power, fiscal credibility, a recovery in credit growth and expansion outside the resources industry mean that the country’s standing is not just the result of growth slowing in Ivory Coast and Ethiopia.

“Ghana has a more diversified economy than a lot of its African peers,” Capital Economics Ltd. economist John Ashbourne said by email.

“Ghana is doing very well — this isn’t just a matter of being the last man standing.”

Oil booms

Ghana’s growth booms and busts have been closely linked to crude since it became an oil producer in 2010, when Tullow Plc started the Jubilee field. Economic growth surged to 14.4 percent the following year, and slumped to less than 4 percent from 2014 to 2016 as oil prices dropped.

What our economists say

“Ghana clearly is having an oil-fueled boom at the moment but non-oil growth is yet to pick up markedly. Its high debt-servicing cost will make it challenging to lift public capital investment despite a large infrastructure deficit compared to many peers,” Mark Bohlund, of Bloomberg Economics, said.

Ghana is the world second-largest cocoa producer, lagging behind Ivory Coast, and produces the most gold on the continent after South Africa.

The government is investing in agriculture and Akufo-Addo has pledged to set up factories in each of the nation’s 216 districts to diversify the economy.

“In 2018, we expect Ghana’s growth story to become more nuanced,” Razia Khan, chief economist for Africa at Standard Chartered Bank, said by email. “There will be much more focus on whether a robust recovery in the non-oil economy manifests itself.”

Deficit targets

Investors will look to see if Ghana can maintain financial discipline after years of chronic overspending.

The country turned to the IMF for an almost $1 billion bailout in 2015 as spiraling debt and high inflation pushed the cedi into freefall after the budget deficit ballooned to more than 9 percent of gross domestic product. While the nation is still at a high risk of debt distress, according to the African Development Bank, it’s on track to meet the fiscal-deficit target for 2017 and has negotiated an extension of the IMF programme until the end of this year.

Narrowing deficit

Inflation in Ghana slowed to 11.8 percent in December from a record 19.2 percent in March 2016, allowing the Central Bank to cut its benchmark rate five times in a year, and the rate of credit growth to the private sector has doubled since August.

This will support expansion in the non-commodity sector, according to Yvonne Mhango, an economist at Renaissance Capital in Johannesburg.

“What distinguishes Ghana from others is the progress it is making in improving its fiscal credibility, by sticking to its targets and implementing other reforms,” she said.