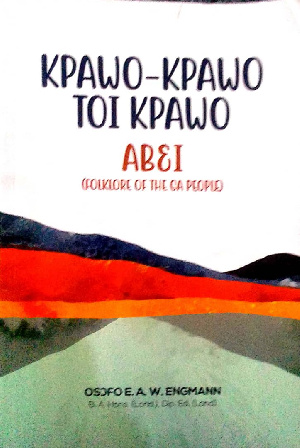

Kpawo Kpawo-Toi Kpawo by E.A.W. Engmann delves into folklore of the Ga people

Kpawo Kpawo-Toi Kpawo by E.A.W. Engmann delves into folklore of the Ga people

When I was growing up in Accra, never once was I made to feel awkward for being literate in Ga or for speaking Ga, which is not my ethnic language.

Sadly today, I have become accustomed to being asked whether I am a Ga indegene anytime I speak Ga in public.

It is a sign of the times for such a question does not make sense.

But I am not naive: stereotypes abound; chauvinism and bigotry are rife in today’s world.

UNESCO has warned us that some languages and cultures are under threat of extinction, and we shall all be poorer for this.

Reverend E.A.W. Engmann, a Basel Mission/Presbyterian priest and educator who compiled this book of 733 proverbs and folklore was a superlative exemplar of Ga language and culture.

Having obtained a Bachelor of Arts, and Diploma in Education in England, he returned home and devoted his life to preparing sermons regularly in Ga; he also taught at Presbyterian Boys’ Secondary School Legon, and elsewhere.

His book was completed posthumously in 2021 by Reverend Dr. Philip T. Laryea.

Having read this book for at least a month now I have completely fallen in love with it; quoting proverbs as one liners for bragging rights is useless because they often come in contradictory pairs.

Accompanying every proverb is a short story of about one paragraph that places the proverb in context and explains how the proverb is used.

Sometimes the story is written in English to offer relevant teaching points.

The book is arranged into five main parts: in part one proverbs about “animals” are presented; part two talks about “plants and wood”; part three is about “domestic articles”; part four is about the “person” and “parts of the body”; and part five is about “general and abstract ideas”.

Then there is a bibliography, index and of course the introductory parts.

The book reveals through the proverbs important information and throwbacks about ancient and modern civilizations; our ecology, plant and animal species including some that have almost disappeared.

It also exposes a rich cross fertilisation of ideas within Ghanaian society.

For example, the foreword shows that Rev. Engmann wrote the book on 30 January 1970 when he was domiciled at Oyamfa, a suburb of Accra that lies along the Accra-Aburi route.

Today that place is commonly called Oyarifa, which means something completely different, almost sounding Akan.

Reverend Engmann, our research reveals, subjected his compilation to rigorous critique by falling on a close family of advisors – a triumvirate or magisterium – who debated the context of each proverb and subjected it to the highest interpretation.

That might partly explain why the sage could not publish the book in his lifetime.

One must, therefore, commend Rev Dr Laryea, – an author, professor and theologian based at the Akrofi-Christaller Institute, Akropong, for earning the trust of the family of the late Rev. Engmann and bringing the book to reality.

There are appropriate photographs of certain animals including the partridge which in my childhood, the “boys boys” used to hunt with difficulty in Mamprobi/Old Dansoman.

Afi, the Ga name for the partridge, is complaining that he is more embittered against the one who plucked its feathers than the one who killed it.

Why?

Because the feathers are so precious to it.

The one who killed the Afi only wanted to have it for a meal, but you have “no reasons” for plucking its feathers and wasting it; except mere jealousy and hatred.

Rev. Engmann argues that this proverb is akin to saying “Art thou Brutus” and is used when one feels betrayed.

Alas, not only is the Afi or partridge virtually extinct in Accra, but its place in history is lost on us.

During Christmas we sing the song “Twelve Days of Christmas” and render the line “And a partridge in a pear tree” without realising that the colourful bird, almost the size of a Guinea fowl lived in marshy, waterlogged, Ramsar sites all around us, and is not only localised to areas where pear trees blossom or where the song originated from.

There is a photograph and proverb about the dung-beetle, but where is the hardy, buzzy, flighty little crustacean today?

Engmann links the wasted efforts of the dung-beetle at gathering food to how humans too engage in fruitless ventures that benefit no one.

As many of the creatures mentioned in the proverbs are now hard to spot around Accra, the import of some of the proverbs will be lost on the present generation.

Is the publication of this book titled “Kpawo Kpawo Toi Kpawo”, to wit 77 times or 70 times seven, not a wake up call for the UNESCO Ghana Office in Accra, and all people of goodwill to rise up and make a never ending attempt at saving our environment, and thus our common humanity?

Engmann provides plenty of cross referencing of one proverb to another; he tells the reader that one proverb is more appropriately linked to some proverbs than others.

He also leaves room for debate about the context and import of some proverbs, creating space for readers to think and ponder for themselves, where he had no answers.

As someone who is also literate in Fante and Twi, the book has convinced me that our indigenous languages share significant commonalities.

There are expressions in Ga that sound like pure Fante to me.

Indeed one of the seven references at the back of the 299 page book is the “Dictionary of the Asante and Fante Language called Tshi (Twi)” by JG Christaller, published 1881.

Kpawo Kpawo Toi Kpawo brings to the fore the excellent role of the Christian Missions in particular in promoting indigenous languages.

In terms of Ga literacy and indigenous languages generally, it is a shame that it is virtually only the Jehovah’s Witnesses who publish Ga material regularly in print and on their website https://www.jw.org/gaa/.

Kudos to Rev. Dr Philip Laryea and his assistants for bringing this excellent book to publication; it is a powerful resource and a valiant attempt towards the preservation and revival of the rich Ga language and culture.