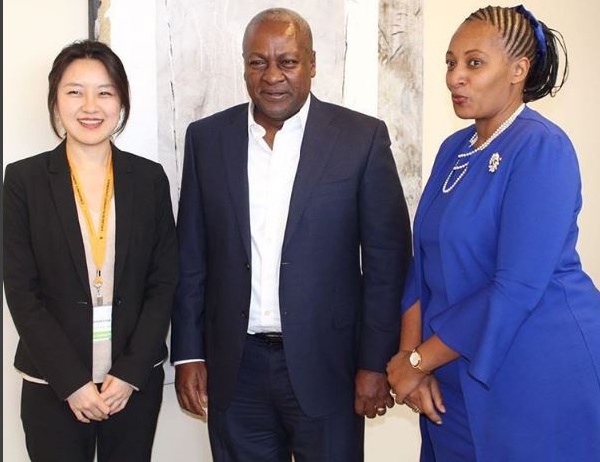

Former President John Mahama with David Axelrod

Former President John Mahama with David Axelrod

By Dele Momodu

Fellow Africans, I have often wondered about what is the matter with most African leaders and rulers that they love to cling to power, by fire by force, as if their very lives depended on it.

An average African leader will never quit power voluntarily, and enjoy a standing ovation, as well as everlasting adulation, no matter the situation.

He would rather subject his country to sorrow, tears and blood, just for him to remain in power. One of the earliest spiritual teachings I learnt as a kid was the Biblical aphorism: “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh!” Whatever has a beginning must have an end. No matter how long you spend in power, you must quit one day, voluntarily, or involuntarily, when your time is up. And your time is up when the Law say it is, not when age or extraneous forces, like coups dictate truncate your heinous rule.

Why then, you may ask, can’t mere mortals understand and appreciate this dictum and spare their people the agony of many years of misrule and sit-tight syndrome?

Let me emphasise that it is not how long you govern that matters but how well. Every leader must decide how he wishes to be remembered. It is pertinent for every leader to consider this and decide on what he can do very quickly to attract eternal grace and praise. Anyone who has studied the history of power would readily know how time flies indeed.

Since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999, President Olusegun Obasanjo has come and left. President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua has come and departed. President Goodluck Ebele Goodluck has done his bit and retired. President Muhammadu Buhari has nearly spent half of his first term, just like that. This confirms my thesis about how quickly time evaporates.

But I’m happy to meet a man who has demonstrated that you come, you serve, you go. It has been a privilege for me to know and work closely with His Excellency, former President John Dramani Mahama of Ghana, before he quit office and now that he has. He is an eloquent example of how a responsible leader should behave in power and afterwards. I met him shortly before he became the Vice President of the Republic of Ghana.

Though a Member of Parliament and Minister at the time, he was reluctant to accept the position. I was invited to his home by our mutual friend, Mr Victor Smith, later the High Commissioner of Ghana to the United Kingdom. Mahama and I became friends instantly. I discovered a personable gentleman who did not see power as a big deal other than as a call to service.

As fate would have it, a man who reluctantly became Vice President would later be catapulted to the seat of President and Commander-in-Chief, without lifting a finger, after the unfortunate death of his boss and mentor, President John Evans Atta-Mills, of blessed memory.

In a jiffy, and without much ado, he settled down quickly to serious work, and continued from where his boss stopped. He not only mapped out his priorities but he produced a road map to achieve them. He understood what Ghana needed to join the comity of other nations in the march towards superlative development and pursued his mission rigorously and vigorously.

He made infrastructure development the cardinal principle of his government and stayed glued to it stubbornly no matter how much others preferred stomach infrastructure. He told his people the bitter truth at every point. He spoke what no politician would have said and what the citizens would not like to hear.

Mahama was a man in a hurry to build a new Ghana. His dream was to surpass the commendable work of his predecessors, especially that of the father of modern Ghana, Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah. Like all mortals, Mahama was not a perfect human being. He had his foibles but was rigidly committed to his developmental projects. He was accused of overlooking the excesses of some of his close disciples who were accused of corruption.

Many expected him to spend time pursuing corrupt people, making heads roll and if necessary make blood flow. However, Mahama chose to concentrate on his goal of societal development through revamping the economy, infrastructure creation and firming up of institutional structures. He was content to leave the established enforcement institutions to tackle all the corruption once he strengthened the system.

He said he knew it was not the job of the executive arm to prosecute and convict and so would not be distracted, or bogged down by a job that largely belongs to other arms, especially the independent and impartial Police and judiciary.

Mahama worked as if he had a premonition of the electoral hurricane that would eventually blow him away, unmindful of his stellar achievements. He modernised the Kotoka International Airport monumentally. Built new regional hospitals. Added about 800 megawatts of electricity to the national grid. He pursued rural electrification with uncommon gusto.

Regraded many roads and established new ones. Upgraded many educational institutions and paid more attention to technical schools in order to train and graduate world-class engineers and artisans. He provided an enabling environment for agriculture to thrive. Access to data services became widespread in rural areas.

On the foreign scene, he opened Ghana to all Africans who are now able to obtain visa on arrival without stress. He stabilised the Ghanaian currency, Cedis, and investors made Ghana a preferred choice because of its stability and tranquillity. He welcomed non-Ghanaians with open arms. He doused the perennial tension between Ghanaians and Nigerians. He encouraged Nigerian businesses to blossom.

As a gesture of genuine goodwill, he awarded the highest civilian honour in Ghana to the spirit of Africa, Dr Michael Adeniyi Agbolade Isola Adenuga, a business prodigy, who has quietly affected Africa with his closely guarded treasure.

As audacious as Mahama was in the area of infrastructure development, he was not able to balance this with putting cash in people’s pockets. The unemployed youths kicked, shouting that they preferred jobs. His explanation that infrastructure would lead to jobs fell on deaf ears. More hospitals, he enjoined, will employ more doctors, nurses, pharmacists, health technicians, administrators, paramedics and so on; more schools would absorb teachers and students alike as well as the requisite support staff; construction would attract engineers of various disciplines, artisans and others.

For him, it was only a matter of time before the jobs sought by the restive youths would come. The long and short of it was that he achieved his dream of modernising Ghana but lost his plum job. His humongous work will never be forgotten and he would always be remembered as Nkrumah II, as he is now fondly called. History has only repeated itself because Nkrumah the Great suffered a similar fate when he was similarly chased out of power. But Nkrumah became apotheosised only thereafter. Everything he did was criticised but the landmarks are there till this day.

Mahama has become a global citizen after leaving power. Since he handed over on January 7, 2017, he has moved from being a Ghanaian leader to being a much sought after international statesman. I’ve been greatly inspired by his meteoric rise on the world stage. I’ve travelled extensively with him in the last two and half months.

The usual Nigeriaphobia has never affected our relationship. Mahama is a rare species and a true Christian who practices the tenets of love. I’m proud to stand with him all the way. His speeches flow from his heart. He speaks extempore and has the facts and figures in his head. We have spent the last one week crisscrossing the best of American institutions.

He spoke and lectured, as the situation demanded, at Harvard, MIT, Boston University, University of Chicago, Chicago State University, The Institute of Politics, The Africa International House, and Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management.

Former Obama strategist, David Axelrod, summed up the story of Mahama, when he climbed the stage to commend his speech at the Institute of Politics, Chicago, delivered to a packed audience of American scholars and influential leaders: “I don’t know what happened in Ghana but if a vote were conducted here, majority would vote for you.” Mahama’s speech was simply awesome. He captured and wowed his audience. The Question and Answer session was gripping. Mahama was honest and candid. He autographed his autobiography, MY FIRST COUP D’ETAT. It was such a glorious and victorious trip.

As someone said, Mahama has glamorised life outside power so much that no African leader should be scared of losing election and fearing what the future holds. If you have done well, the world will be your oyster! Mahama’s own reaction continues to resonate: Your duty as a leader is to come, serve and go…” I concur.